Why Cellular Spectrum Matters for Community-Centred Networks

Walk past a township school in South Africa, and you might notice kids pressed up against the fence, phones in hand, trying to get a good signal on the free school WiFi network. It’s an image that says a lot. Affordable internet isn’t just about price, it’s also about where you can connect. At the end of the day, meaningful connectivity means being able to go online from your home, using your own devices, such as laptops, tablets, and phones, without having to trek to a hotspot.

Across South Africa, community-centred networks and small internet service providers have been expanding affordable access to townships and far-flung rural areas. Most of these providers rely on WiFi-based technology, setting up local hotspots or fixed wireless links to household rooftops for users who can afford monthly subscriptions.

For many low-income households, WiFi hotspots don’t provide reliable coverage indoors, and rooftop installations are unaffordable for those unable to commit to monthly fees. That means most low-income households have to fall back on buying small bundles of expensive data from the major mobile operators.

New developments in cellular spectrum in South Africa

This is where things could really shift. Imagine if community-centered networks had access to the same spectrum that the major mobile operators use. With this spectrum, they could roll out small cellular base stations inside their own communities. Suddenly, people could get affordable connectivity not just at public hotspots, but at home, walking down the street, or wherever they go in their neighborhood.

And here’s the good news: momentum is building; in South Africa, thankfully, policymakers have recognized the urgency of addressing digital inequality and the need for spectrum reform:

● In May 2024, the government published the Next-generation Radio Frequency Spectrum Policy for Economic Development. It specifically recognized the role of community-centered networks and called for IMT spectrum (the bands used for mobile broadband) to be released to them.

● Then in March 2025, ICASA followed up with Draft Regulations on Dynamic Spectrum Access and Opportunistic Spectrum Management. These include IMT Band 77 (3800–4200 MHz) and emphasize lowering barriers for SMMEs and community-centered networks.

All of this points to a critical turning point: community-centred networks could soon be able to use cellular technology to bring low-cost access to low-income communities

Not all spectrum is created equal

Physics plays a big role. Different frequency bands work in very different ways, and the types of devices that support them make an equally important difference.

● Low-frequency bands (like 600–700 MHz) travel far and cut through walls, buildings, and trees. They’re great for coverage but don’t have much capacity. They also require costly specialized equipment that currently only supports fixed wireless links to rooftops. In theory it may be possible to support smartphones in the future but low-cost phones in South Africa don’t currently support this band.

● High-frequency bands (like 3800–4200 MHz, the new Band 77 mentioned in the draft regulation) supports high speeds greater than 100 Mbps and are well-suited for dense neighborhoods. But they don’t travel far, need line-of-sight, and are only supported by a small fraction of high-end smartphones.

● Mid-bands (like Band 41 at 2.5–2.7 GHz) are the sweet spot: good coverage, decent capacity, and, most importantly, supported by the kinds of affordable smartphones that dominate in townships and rural areas.

The South African spectrum landscape

The regulatory picture in South Africa reflects this mix. The 600–700 MHz band (TV White Space) is already available for fixed wireless links under dynamic spectrum access rules. Band 77 is next in line, also on a dynamic spectrum access basis. But both of these bands face challenges: without major changes in which bands low-cost phones can use, they won’t significantly reduce the cost of access for low-income households.

At iNethi, we still see these two bands as important parts of the broader spectrum ecosystem available to community-centred networks. In time, as more phones begin to support them, they could play a bigger role. If that happens, community-centered networks will be able to combine different frequencies to balance coverage and capacity — just as the major mobile operators already do.

By contrast, opening up a mid-band like Band 41, already supported on most low-end phones, could be transformative. That’s why we at iNethi, with support from the Internet Society, have applied for a test license in an unused 20 MHz portion of this band. The goal is to demonstrate the impact community-centred networks can have when given access to cellular spectrum that is supported by most phones in low-income communities. Our plan is to deploy low-cost cellular technology using Band 41 in two township communities and two rural communities in South Africa during 2025/26.

On top of this, we’re developing innovative open-source tools designed for community-centred networks that want to roll out this kind of technology. We’re integrating Open5GS with our iNethi platform, which already provides access to free, locally hosted content and services through a community cloud server. The platform also supports single sign-on, multiple payment options — including community vouchers — for buying internet services, along with authentication and accounting through our partnership with Radiusdesk. We’ve already made some good progress on this — check this piece from Keegan White, the lead developer on the project: “Reimagining Community-Centered Networks with Community-Owned Cellular”

Lowering barriers for community-centered networks

Fair licensing models are just as important as the spectrum itself. Communities need affordable, flexible fee structures, exemptions for non-profit operators, and straightforward processes that don’t bury small players in red tape.

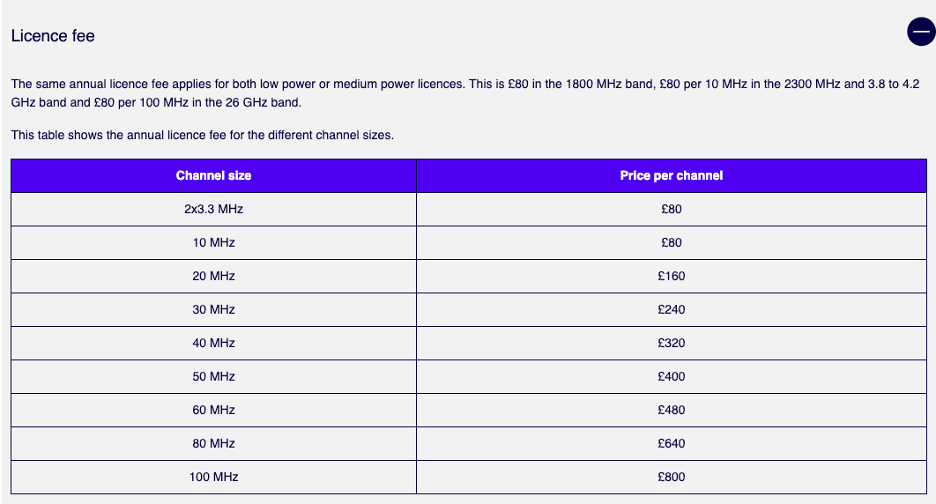

The UK’s communication regulator, Ofcom, provides a strong example. There, shared access spectrum licenses are available in the 1.8 GHz, 2.3 GHz, 3.8–4.2 GHz, and 25.25–27.5 GHz bands. They cost as little as £80 per 10 MHz per site per year, and the licenses remain valid indefinitely as long as fees are paid. This kind of simple, predictable framework shows how spectrum can be managed in a way that is both sustainable and accessible.

A call to Action

Community-centred networks are not just about technology; they’re about equity, dignity, and giving people a real chance to participate in the digital economy. They create socio-economic upliftment for both the end users who gain affordable access, and the local operators and entrepreneurs who build and maintain them.

To unlock this potential, spectrum policy must reflect the realities of low-income communities:

● Open up spectrum that affordable devices already support.

● Create flexible licensing models that keep costs low for community-centered networks and small operators.

● Adopt international best practices while tailoring them to South Africa’s context.

The TV White Space band and the new Band 71 in the innovation spectrum are promising first steps. But true digital inclusion will only happen if regulators go further — opening up spectrum in bands that actually work for the people who need it most.